PORTSMOUTH, New Hampshire — It’s after 10 a.m. on a Thursday in December, and Asa Hutchinson is making his entrance at his first campaign event of the day: a visit to the Golden Egg Diner.

Inside, one enthusiastic supporter is waiting to greet him, as is a man who collects trading cards of politicians and asks Hutchinson to autograph a set bearing his image. The cards are emblazoned with a “Decision 2023” logo.

Hutchinson signs the cards and sends the man on his way, turning to a sparsely filled restaurant. There is no crowd of curious Republican primary voters lining up to meet him. No stage, no microphone, not even a clipboard with a sign-up sheet.

There is the 73-year-old former Arkansas governor, his driver for the day, and a trickle of customers he would need to interrupt with his elevator pitch while their plates of eggs and toast got cold.

In a 2024 presidential primary defined by longshot candidates, Hutchinson may be the most stubborn of all, still plowing forward while barely registering in the polls. His candidacy is testing the limits of just how long a dignified, accomplished conservative — the kind who brought a southern state’s Republican Party into relevance — can withstand rejection from his own party’s base. And it’s all in the hope that somehow, some way, his message will break through.

“Have y’all made up your mind on the race yet?” Hutchinson asks the first table he approaches, two men sipping coffee, after running through an abbreviated version of his resume: Reagan conservative, former governor, former head of the DEA and former congressman who wants to take the Republican Party in a “different direction from Donald Trump.”

One of the men, who identifies as an independent, says he plans to support Nikki Haley. Hutchinson says he likes her, but proceeds to make the case against her. She wants to repeal the federal gas tax and limit trade with China, he says. And besides, he was the only candidate — not Haley — to refuse to raise his hand at the first debate when the candidates were asked if they’d support Donald Trump as the nominee, if convicted.

That was back when Hutchinson could qualify for a debate. He hasn’t since August, and the other man at the table, an independent who is undecided, is fixated on Hutchinson’s polling performance, asking him about it twice in the course of their conversation.

“Still polling low, so I’ve got a long way to go,” Hutchinson tells him.

The man tells Hutchinson to “keep plugging,” and recalls meeting another Arkansan, Bill Clinton, in New Hampshire in 1992. “It went OK for him,” he adds.

After Hutchinson thanks them and walks to another booth, the undecided voter, who declined to give his name, said he didn’t recognize Hutchinson when he approached.

“Honestly,” he said, “I wasn’t even aware he was running.”

A seasoned politician who has held federal and state offices since 1982, Hutchinson is polling at less than 1 percent in national and early-state polls. He boasts the endorsement of a single elected official nationwide, a New Hampshire state senator. His message of moving on from Trumpism gets him booed at conservative activist events.

But unlike higher profile Republicans who dropped out of the presidential primary after failing to gain traction — including former Vice President Mike Pence and Sen. Tim Scott — Hutchinson isn’t ready to stop running. The question he now faces is why?

Back over the week of Thanksgiving — a deadline Hutchinson had previously set for himself to reach 4 percent — I asked him if he worries how his run for president will frame his legacy, one that could have ended with a two-term governorship after a four-decade career in public service that began with being appointed U.S. attorney by former President Ronald Reagan.

“You’re asking me about risk of embarrassment? People have risked their lives for the country,” Hutchinson said. “Am I supposed to worry about whether I’m going to be embarrassed in a contest, politically? I think our country is more important.

“I don’t want to turn our country or party over to Donald Trump or Joe Biden. That’s what I’m saying, and it actually reflects what the polls say in America.”

And that, Hutchinson maintains, is the reason he is subjecting himself to all of this: to last year’s worth of hotel room stays, and walking up to unsuspecting diners with wads of business cards, and speaking to seven people in a public library event room — as was the case a couple days earlier, when he held a town hall event in Plymouth, New Hampshire — and the general indignity of running for president with almost no one seeming to notice.

After leaving the diner that Thursday, Hutchinson was on to a larger affair, a crowd of 40 at the Portsmouth Rotary Club.

A few months ago, when it became apparent Hutchinson wasn’t going to make the second debate, multiple people close to him, who were granted anonymity to speak freely, began suggesting he explore other options for his post-gubernatorial life. He could easily get a paid commentator gig. He could become a full-time surrogate for another Republican candidate. He could start working to open a Hutchinson Center for Democracy at the University of Arkansas. He could play golf every day.

His campaign offered to set up phone calls for him with other candidates in the event Hutchinson would consider getting out and endorsing someone else, according to a person with knowledge of those conversations.

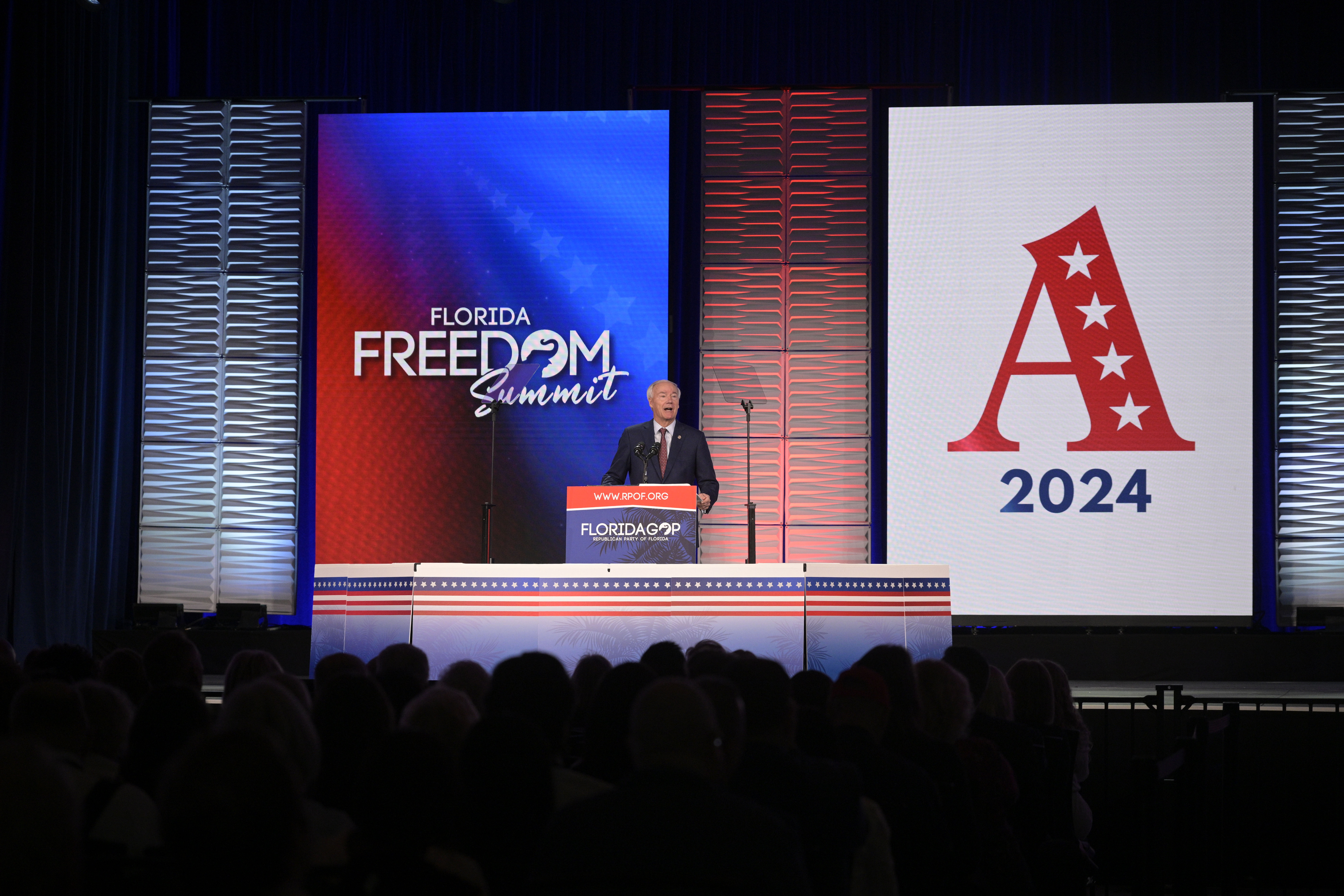

Despite a cash crunch for the campaign, Hutchinson was set on paying the $25,000 fee earlier this fall to get a spot on the Florida primary ballot — which also included a spot on stage for an event hosted by the Florida GOP. The campaign had already let a staffer go and closed its Bentonville, Arkansas, office, according to a person with knowledge of the campaign’s operations. Ahead of the Florida event, Hutchinson’s campaign manager, Rob Burgess, stepped away from the campaign over disagreements about how — and whether — to proceed with a presidential bid. Hutchinson still decided to take the stage, where he faced intense jeering for speaking out about Trump’s legal troubles.

Burgess, in an interview, suggested that the response shouldn’t have been surprising.

“Asa Hutchinson would have been a great candidate in 2012. He would have fit the party of 2008 and 2012 perfectly,” he said. “And now he finds himself running for president as a Reagan conservative in an era when Reagan conservatism isn’t cool anymore.”

There are few people who will disagree that Hutchinson is well credentialed, and also kind and friendly. Even an official with the Teamsters labor union, where Hutchinson met with both officers and rank-and-file members in D.C. (so far, the only Republican presidential candidate to do so this cycle) the day after his diner and Rotary visits, described him to me as “very nice.”

“He’s an extremely nice guy, personally,” Dave Carney, the veteran New Hampshire Republican strategist, told me. “I just don’t know how he looks at the situation and says ‘here’s my pathway.’ There is no pathway for him.”

When I suggested to Carney that Hutchinson wants to force a conversation about the future of the Republican Party, he shot back with a less sympathetic response.

“I have a point to make too, but no one gives a fuck what I think,” Carney said. “I can go stand on my front porch and shout for an hour and no one’s going to pay attention.

“This is a serious thing. Being president of the United States is serious,” Carney continued. “If you think Trump is the evil bastard that you say he is, then what are you doing? ‘Ruining our democracy,’ whatever Gov. Hutchinson says — if you believe that, you’re helping him by staying in.”

Hutchinson insists he is playing a long game.

He didn’t file in South Carolina or Nevada. But Hutchinson has qualified for the ballot — sometimes at great expense to a campaign that is operating on such a lean budget — in states including Massachusetts, Michigan, Florida, Georgia, Colorado, Texas, North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas. While inside the diner, Hutchinson stepped out into the entryway to take a call from the Ohio Republican Party chair to discuss ballot criteria.

At the restaurant in New Hampshire, I overheard him tell a pair of diners that his goal is to come in fourth place in Iowa. Hutchinson noted that I was eavesdropping and conceded that he has not previously disclosed this strategy publicly.

“But yeah. I want to beat expectations. And, you know, maybe we can do better than that,” Hutchinson said. “But I think that if we came in fourth place, then that means we’d beat expectations.”

In reality, his idea of how he could win the nomination is even more of a bank shot.

Hutchinson is firm in his belief that Trump will be convicted of a crime next year, likely after what are expected to be big wins for him in multiple early states. And whenever it happens, he said, he suspects more candidates will have already dropped out. Should those series of events take place, there would be one candidate with impeccable anti-Trump credentials and firm conservative convictions still standing: Asa Hutchinson.

“I don’t know when that’s going to be. In April? Mid-summer? Whether that’s going to be in the fall after the convention,” Hutchinson said, after passing me half of a breakfast club sandwich he determined was too large. “But as long as I am able, I want to provide that alternative voice. And I’m not sure other candidates have that same level of commitment.”

After an entire summer spent hustling to come up with the required 40,000 donors to get on the first debate stage, the super PAC supporting Hutchinson, America Strong & Free Action, effectively disbanded. The group had spent nearly all its money to put Hutchinson over the qualifying threshold, but the former governor didn’t give a breakout performance.

“He was a longshot who had this phenomenal resume, who had a story to tell from rural America, and that hasn’t changed,” said Austin Barbour, a Republican consultant who worked on the super PAC supporting Hutchinson. “This is not about what I believe or you believe, it’s about what he believes. He’s the one who will ultimately be participating in the caucus in Iowa.”

Jon Gilmore, who served as a longtime aide to Hutchinson in the governor’s office, told me his former boss is trying to “keep the Republican Party from being hijacked by personalities,” and “when you hear him say that, whether you like him or don’t like him, or like Trump or don’t like Trump, it’s hard to argue with that sentiment from someone who has fought for the party that long.”

Gilmore continued, “It’s up to Asa Hutchinson to decide how long he should stay in this race. For any candidate running for president, it’s their rodeo. Let him ride as long as he wants to ride.”

For now, Hutchinson is riding alone. Or at least flying that way, as his campaign counts every dollar to conserve its meager resources.

Hutchinson has largely been navigating airports by himself for the last couple of months, or “with the American public,” as he put it, which he said came as a relief after eight years of having a security detail as governor. I saw him in October wandering alone around Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks’ fundraiser in Coralville, Iowa, passing out business cards.

More recently, When I asked Hutchinson about his critics’ main argument — that he is enabling Trump by not helping consolidate the field behind a higher-polling alternative, he brushed it off. Too many people want to cut the voters out of the process, he said, and besides, there has already been a consolidation through the “natural process,” pointing to his one-time opponents Pence, Scott, Doug Burgum and others who dropped out this fall.

With a vote share of less than 1 percent, there’s only so much splitting of the vote that Hutchinson can do, anyway.

As the Jan. 15 caucuses approach in Iowa, Hutchinson told me he believes he can peel off supporters of Christie, Haley and Vivek Ramaswamy, in particular. He said he will remind Iowans that Christie — whose message is most similar to Hutchinson’s — hasn’t bothered to campaign in Iowa. And Ramaswamy, Hutchinson said, has become consumed by conspiracy theories — now “a different person, actually, than even when he started campaigning.”

When he defended in November his decision to stay in, Hutchinson told me he “looked at the grassroots momentum that I sense that we have.”

It’s hard to find much evidence of that. When I asked Tim Coonan, Hutchinson’s Iowa state director and friend since the George W. Bush administration, how things are looking on the ground there, he acknowledged that few of Hutchinson’s events involve the former governor as the main attraction. It’s often him showing up to make his case where people are already gathered.

“It’s difficult to get attention. It’s not flashy. It’s not headline grabbing,” Coonan said of Hutchinson’s campaign to date. “But my concern would be if this wing of the party went silent.”

If a dose of political humiliation is the price to pay for ensuring that there is a credible non-Trump voice in the 2024 primary, then Coonan, at least, is happy that someone is willing to pay it.

“Imagine a world where all the Asa Hutchinsons decided to pack up and go home,” he said. “I certainly don’t think that would be good for the country.”

11 months ago

11 months ago

English (US)

English (US)